Super EGA: An Ongoing Series on What the Hell I'm Up To

Ever since I started this space, I’ve been meaning to sit down and talk a bit about the nature of my current project. Being as my bursts of hard work on the thing are often brief and sporadic, it’s difficult to nail down a few hours to just document the endeavor. Now that it’s been 14 long months and four whole other entries to the blog, I’m forcing myself to channel this most recent momentum into a little explanation.

As with every post I’ve written, I set out to write a short and snappy little treatise on the important bits but then got 200 paragraphs in and decided to break it up. So the first bit of my documentation of the project will be a bit of a history lesson. Please enjoy.

CGA, EGA, VGA: A (Perhaps Not So) Brief History Part 1: CGA

The rise of the IBM PC

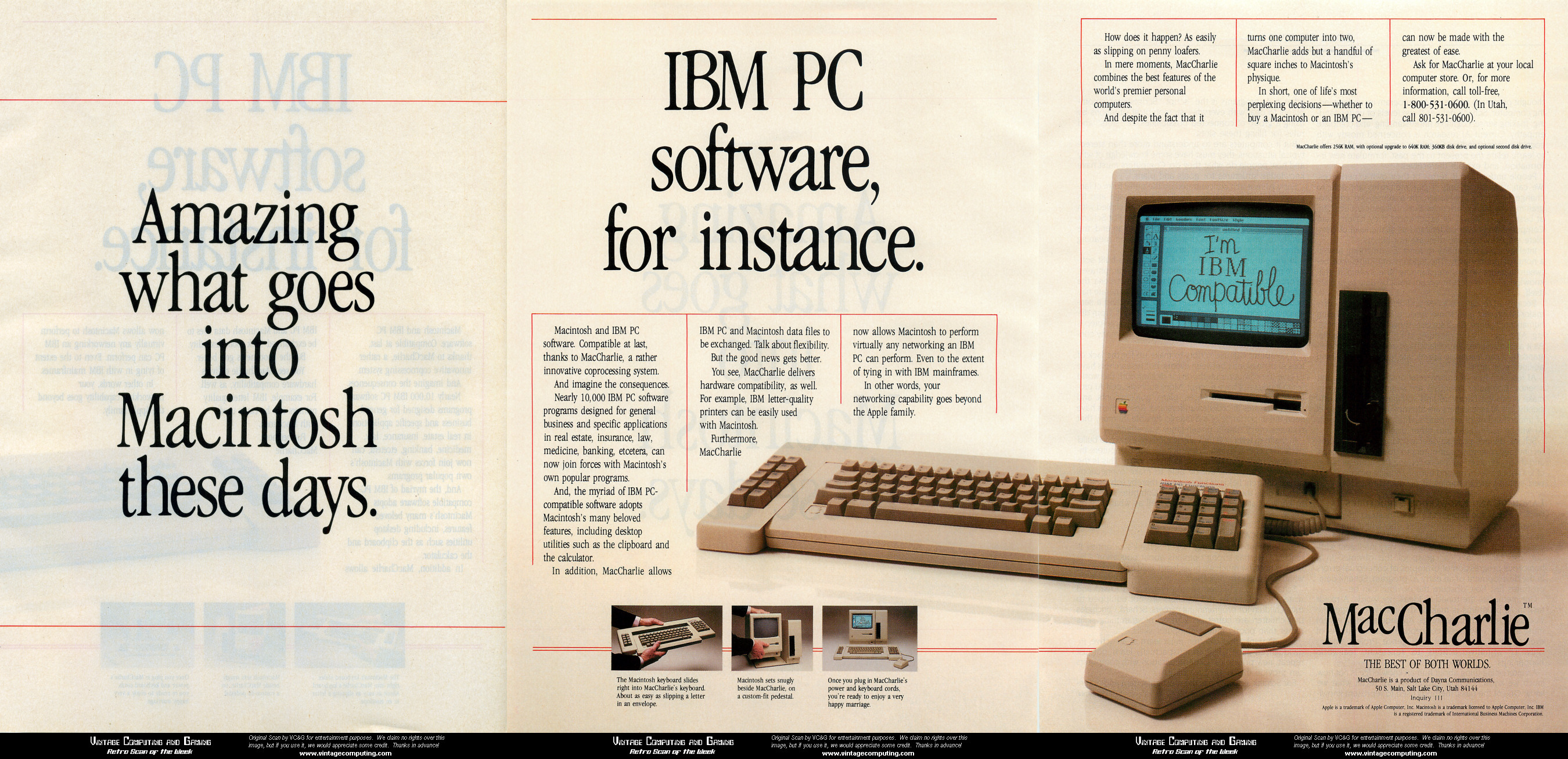

![]()

12th of August, 1981. The Original IBM PC, Model 5150, entered the infant “microcomputing” market1. It was considered a play by IBM to attempt to compete in a space largely dominated by Apple, who enjoyed legendary success with the Apple II in 1977. The 5150 sported 128 kB of memory, a 4.77 MHz Intel 8088 Processor, a 5.25” floppy drive, an on-board PC Speaker, and retailed for 2-3 thousand dollars. Perhaps most importantly, the cheapest and most popular operating system available for the 5150 was PC DOS created by the 5-year-old Microsoft on commission from IBM.

The details of IBM’s commission allowed Microsoft to go ahead and sell their own version of PC DOS, called MS-DOS, for use on non-IBM computers. IBM then encouraged software developers to write programs for DOS, rather than specifically for the IBM PC hardware, with the goal being that software could run on any machine running DOS. However, code accessing the hardware directly was universally faster than going through a standardized software layer. Given the overall success of IBM PC sales, developers were justified in taking advantage of this increase by making their software, especially games where speed is perhaps most crucial, target IBM PC hardware directly.

What followed was the age of the IBM PC-Compatible Computer. Microcomputer manufacturers, in order to compete, created machines that both ran MS-DOS and mimicked the hardware needs of its most popular software. By 1983, the market was beginning to fill to capacity with “PC Clones” from companies like Compaq, Tandy/Radio Shack, Hewlett-Packard, and Texas Instruments. When supply and the pricetag of the 5150 and its successors failed to meet demand, many users opted for the cheaper alternatives.

By 1983, IBM was a dominating force to be reckoned with. It “devoured competitors like a cloud of locusts.” This was only further solidified by the release of DOS 2.0 running on the 5150’s successor, the XT. The XT came equipped with it’s own internal hard drive and was more competitively priced. By 1984, IBM reported $4 billion in PC revenue, more than most of its competitors that year combined.

For software developers in the 1980’s, the market was becoming, for the first time, a largely uniform one. Most computers were either IBMs or could run IBM programs. This meant one of the largest install-bases (potential buyers of a given piece of software) that had ever existed. As PC sales increased, so did the money in its software, and so did the incentive to make more.

Not to get ahead of ourselves, it’s important to note that this all didn’t happen overnight. The rise of the PC was perhaps more of a crawl over the course of a decade; a crawl primarily made by businesses and dads. Compared to Home Computers like the Commodore 64, the IBM PC was expensive at launch. It generally failed to make its way into a majority of households in ‘81 simply because it cost thousands of dollars. It’s acceptance didn’t begin to truly take off until the release of the XT in 1983 and didn’t earn it’s universal acceptance and permanence until the introduction of VGA in ‘87 and ‘88.

I like to think, however, that its initial boost was helped, if only a little, by the brutal and unsightly death of some other companies.

The Fall of the Home Computer

You can read a thorough investigation here. In the early 80’s it began to occur to consumers that the Ataris, Commodores, and Calecos of the world weren’t so much “Home Computers” as just “Video Game Machines.” Increasingly they were marketed to children and their fathers as a toy.

Meanwhile, Microcomputers were becoming available in increasingly affordable options. Not only could they play games, but they also had impressive software suites for home offices and businesses. Magazines began to ask why families should spend their money on a machine that did so much less.

Now I don’t mean to editorialize, there were many varied and complex causes behind the crash of ‘83. Nonetheless, it’s important to understand that games for DOS were quite insulated from the recession. In the two years before Nintendo released the NES in North America and rebooted the console market in a massive way, DOS games enjoyed a comfortable era. You didn’t need to convince mom and dad to get a computer to play King’s Quest, they already had one because it had Lotus 1-2-3 on it.

Graphics Standards and the Video Games who loved them

CGA

The 5150 came equipped with IBM’s first ever graphics card, the IBM Color/Graphics Monitor Adapter. The card introduced a graphics standard which would be come to be known as simply the Color Graphics Adapter, or CGA. This card boasted a stunning 16 kB of dedicated video memory which allowed it to render either a resolution of 320x200 with 4 colors from a 16-color palette, or an astounding 640x200 resolution with 2 colors.

Color in CGA is 4-bit. I’m going to try not to go too deep into how binary data is stored or read here but hopefully if you’re not up on your bitwise, it’ll still make sense. 4-bit color in this scenario means that every color the card can display is composed of four boolean yes/no values. These are red, green, blue, and intensity, also called RGBI or “Digital RGB”.

| Intensity Bit | Red Bit | Green Bit | Blue Bit | Binary Value | Decimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0000 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0001 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0010 | 2 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0011 | 3 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0100 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0101 | 5 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0110 | 6 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0111 | 7 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1000 | 8 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1001 | 9 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1010 | 10 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1011 | 11 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1100 | 12 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1101 | 13 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1110 | 14 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1111 | 15 |

As you can see from my highly flamboyent chart: by using every possible combination of all 4 bits, you come out to 16 possible colors to display.

“But Brandon”, you might say, you estute reader you, “You said that the CGA card had 16 kilobytes of video memory and if you have 4 bits for each pixel then that would need 320 x 200 x 4 = 256,000 bits! That’s 32 kilobytes, not 16!”

Right you are. But if you paid close attention, you may have also noticed that I didn’t say it rendered with 4-bit colors, I said it rendered with 4 colors. Every pixel in video memory was only given 2 bits whose possible values can only be 00, 01, 10, or 11 or, in decimal, 0, 1, 2, or 3. Since every pixel used 2 bits, not 4, you only need 320 x 200 x 2 bits, which is 16 kilobytes on the dime2.

How then, is CGA considered 4-bit color? For that we need to talk about palettes because they’ll come into play for EGA and VGA as well.

Palettes

CGA’s 4-bit color allowed an RGBI monitor to show any of 16 colors on a pixel on the screen. But there wasn’t enough memory for all 64,000 pixels to each have its own value from 0 to 15. Instead, each pixel can only have a value from 0 to 3. To get around this, the user chooses 4 of the 16 available colors that will be displayed at a given time.

For example, if I chose 1:blue, 2:green, 4:red, and 15:white as my 4 colors, I can now render some 2-bit pixels. Each pixel has a value 0-3 so we can use that value as indices into my list of 4 chosen colors. Pixels with a value of 0 will be rendered with blue, 1’s as green, and so on. In display standards, this set of chosen colors to use is called a Palette.

The important thing to remember about a palette is that I can change the palette very quickly just by modifying my four 4-bit palette values. This can change the entire screen’s colors without having to edit the video memory. The next time the screen refreshes, all the values of the pixels will be unchanged but will display different colors because their palette indices are pointing at different colors in a different palette! If you’ve ever heard the term ‘palette-swap’ to refer to similar images being reused in a game with altered colors, this is the same concept.

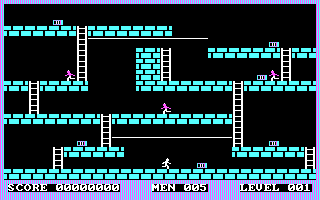

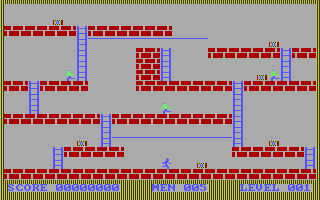

However! CGA cards did not let you set the palette yourself (mostly). There were 2 hardware-defined palettes to choose from, palette 0 was black, green, red, and brown, and palette 1 was black, cyan, magenta, and light gray. This is where you get the wonderfully atrocious looks of some early CGA games:

You could get around these two options a couple ways. First, you could flip the intensity bit which would then apply to the whole palette and give the brighter versions of those 4 colors. Second, CGA offered a special composite burst color bit for use with composite monitors. Disabling this bit would cause the color to be monochrome on the intended Composite TVs but would enable a 3rd palette of black, cyan, red, and light gray on RGB monitors which was far easier on the eyes than magenta. This RGB-only palette could also be used with the intensity bit for a brighter version which brought the total number of palettes available to 6. Finally, palette color 0, defaulted to black, was always used as the background color and it could be set to any of the 15 other colors as desired.

Developers used a lot of techniques and hacks to work around the color limitations. This included rapidly changing the background color for flashing the screen and precisely timing palette-changes during the middle of rendering scan-lines on the screen to overcome the 4-color limit.

RGBI Monitors and the Appealing Brown

The above 4-bit color scheme only works correctly if you plugged the card into an RGBI monitor. But when the CGA was released in 1981, IBM didn’t sell RGBI monitors and users were expected to plug the RCA output into an RF Modulator and plug it into their TV. This conversion had a variety of effects on the colors such as a loss of hue and purity in color. Instead, many people would just use simpler and cheaper RGB monitors which didn’t support the 4th intensity bit. This would effectively limit the available colors to 8, disabling the brighter 8 colors. This would not be resolved until March of 1983 when IBM introduced the Personal Computer Color Display.

Another fun little quirk of CGA is color 6, brown. Using the 4-bit interpolation algorithm of CGA, red-green should produce #AAAA00, a dark yellow. To account for this, RGBI Monitors (including the IBM one released in ‘83) included special circuitry to halve the green component of color 6 to produce a more “visually appealing brown” with #AA5500. You could always tell a cheap, low-rent monitor because it would leave out this circuitry to cut cost and show the wrong color.

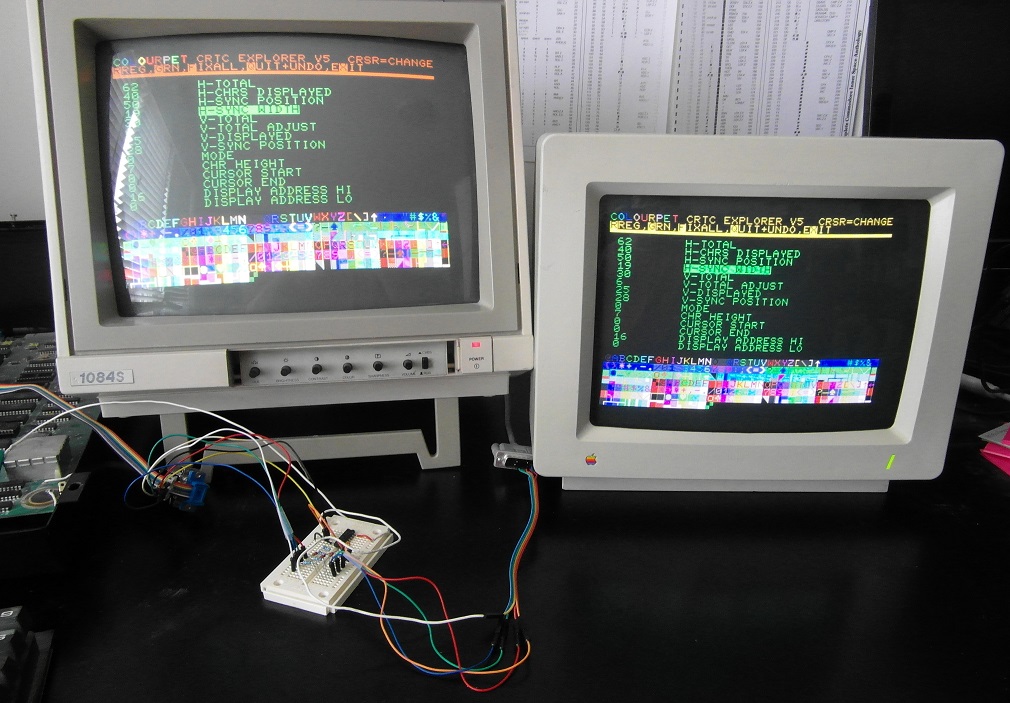

Hercules

A notable competitor to the CGA card was the much-better-named Hercules Graphics Card, or HGC, released the following year in 1982. Much of what made the Hercules popular had to do with Text Modes, which I haven’t touched on during this. Simply put, it was far less difficult to render text because you were simply copying glyphs onto a monospaced grid. At the same time as the CGA card, IBM also released their Monochrome Display Adapter (MDA) card, which offered a higher, sharper resolution than CGA, but could only display text. CGA had a text mode but lower resolution. At the time, many business not interested in games or graphics opted for the MDA because it was easier on eyestrain.

A slight problem with the MDA/CGA split is that some programs did not support both cards because they hadn’t been coded to check and provide different display modes. What this forced some users to do is buy both cards and run a second monitor.

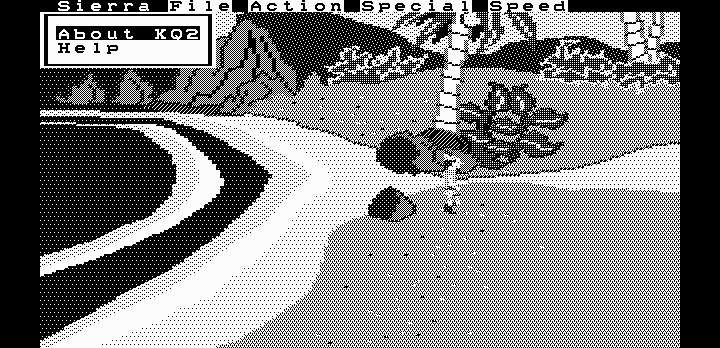

HGC partially solved this issue by first and foremost being a MDA-compatible monochrome card. However, with some post-release driver support, the HGC was also able to run programs that used the common CGA graphical modes. Now Hercules had no color circuitry so the CGA renders were all in various shades of dithered monochrome gray but that didn’t stop the card from becoming wildly popular. The ability to do both high-resolution text and graphics made it the de facto standard on PC Compatibles. As such, many games and software included Hercules-specific display mode options.

Legacy

With the rise of the IBM PC and its “Compatibles,” CGA-powered DOS games flourished for most of the decade. Every PC had BASIC on it, just like the Apple II, and it continued a growing trend of hobbyist programmers taking a stab at game development. After all, the little game you wrote in your basement on your Tandy would (probably) work on your neighbor’s Compaq. All you had to do was copy it to a floppy disc.

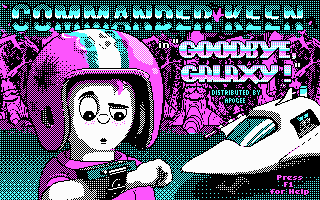

Many games developed for 8-bit home computers were ported to run PC but this was notorious for sub-par versions of the games. PC’s could overall do more than a home computer but often lacked the specific hardware that allowed those games to run correctly. Meanwhile, series such as Elite (later released as Elite Plus in 1991), Commander Keen, King’s Quest, and Ultima found comfortable homes on DOS.

When CGA was replaced by its successor, EGA, the price of CGA cards dropped dramatically and found their way into more and more budget PC-compatibles, further growing the install base. Additionally, the new format (which we’ll talk on soon) was able to provide the old colors and palettes for backwards compatibility which meant that not only did CGA games enjoy compatibility on newer hardware, newer games would offer CGA modes to allow them to still be played on the old cards. The CGA format continued to be supported all the way through 1990.

-

Companies began to settle on the term Microcomputer to distinguish the new machines from the popular “Home Computers” of Atari and Commodore from the 70’s, which had a recognition of being budget and not very powerful. This became even more important after the North American home computer video games crash of 1983. ↩

-

All 16 kilobytes of video memory are in one contiguous block of memory. This block is arranged by 2 bits per pixel, 320 pixels per scan-line (320 x 2 / 8 = 80 byte scan-lines) and 200 scan-lines in the buffer. The scan-lines are also interleaved; the first 100 lines are the even numbered lines and the second 100 are odd. ↩